In the winter of my junior year of high school, all student-athletes got out of class to see some sort of “Excellence Assembly.” It turned out to be something like a TED-Talk, except the presenter appeared to have a passionate and personal hatred for each and every one of us. His speech jumped wildly between topics, veering from drug use to social media to nutrition to sleep to exercise, but on each point he had a consistent message: there was a right and a wrong way to do these things, and we were all doing it the wrong way. He personified the right way as some U.S. Marines that he’d known, who he described as perfect human machines who rarely talked and never laughed and always marched in perfect formation.

In case it isn’t clear, I despised this presentation, and as soon as it let out I wrote an editorial response that I planned to send to the student newspaper. I don’t have it saved anywhere (though, given my writing at the time, I bet it was hardly more intelligent than the presentation itself), but I still remember the last line: “After all, someone has to defend having a good time.”

In the end, I decided not to try to publish it for two reasons. First, if anyone who didn’t know me read it, they’d dismiss it as another lazy kid trying to find an excuse to be lazy (“Teenager DislikesBeing Told What to Do” is hardly headline news). And, second, anyone who did know me would know that I was the last person to defend having a good time. I hardly ever missed a day of cross country practice, never turned an assignment in late, and my idea of a splurge was to push my bedtime back to 10:00 and watch two episodes of The Simpsons in the evening instead of just one. Not to mention that due to my OCD (undiagnosed at the time, but still very much present), I was probably even more obsessed with doing things the right way than the presenter, though my right way mostly focused on the number thirteen in some way.

But an important factor of my OCD is that it only affects what I do. Sure, I’ll be certain something terrible will happen if I stop reading a book on page thirteen, but I don’t care if other people do what they will with that number. But there are a lot of people like that TED-Talker who can’t stand other people doing things the wrong way, however trivial the difference between right and wrong is. You run into these kinds of people often in schools: class picture photographers who spend an hour making sure everyone has the same expression and proper posture, choir directors who demand a hyper-specific dress code, coaches who publicly shame anyone doing the drills wrong. What’s worst is when these people in charge try to be enthusiastic about their strict and arbitrary rules, those teachers who explain the proper way to write a cursive G with a huge smile on their face, not because of any use this letter has, but because the pointless act of writing a cursive G is somehow supposed to be fun. There’s actually a fairly popular and respected teaching technique called behaviorism that is essentially this: embracing obedience as a virtue, rewarding the right behaviors and punishing the wrong ones, while leaving the student with no uncontrolled choices.

OCD aside, it’s strange that I get so mad at people who value obedience. After all, I want to be a teacher, and even if I’m not a full-on behaviorist, no one can run an effective classroom without some emphasis on obedience. I guess it’s the arbitrariness that frustrates me, how the rules are supposed to sit invincibly once they’re laid down. But that arbitrariness is necessary sometimes. I ran into that problem teaching basic literacy skills to elementary schoolers this summer. Capital letters and silent e’s seem perfectly natural to me, but I’ve seen firsthand how much students despise constant correction, even if it is the only way to learn. There’s no way to make it not arbitrary either: I love it, but I have to admit that English writing makes no sense at all.

As useful as obedience is, I think that it’s overused, especially in schools. Having a little room for natural deviation or a little time for slacking off is a necessary resource for sanity. When possible, teachers should enforce the least strict version of the rules, or at least explain why it exists in the first place. I get that it’s probably premature to lay down my laws for teaching before actually doing it on my own yet, but maybe it’s best for me to lay it down now, before life as a teacher grinds away at me too much. After a few years of not being a student, I might be in danger of forgetting what it’s like to be bossed around all day, and I never want to end up like the irate TED-Talker.

great post! I totally agree. Obedience sucks!

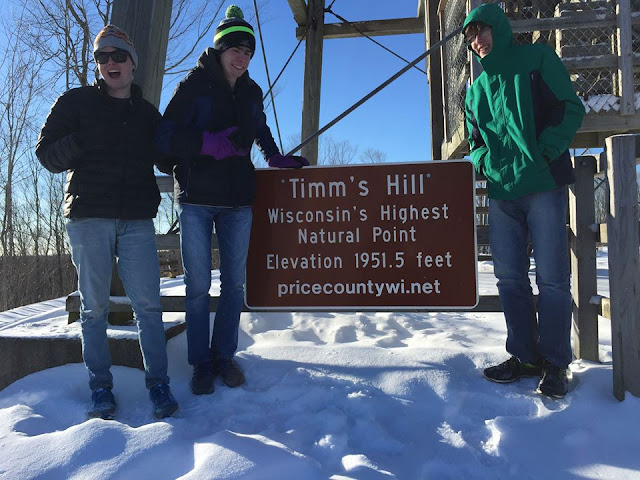

ReplyDeleteTimm's Hill, however, was awesome. I think that was the same trip where you broke into the Mystery Spot and discovered the mystery.

ReplyDelete